The SF/F Watcher’s Lament

Aug. 11th, 2025 01:09 amOf all sad words of tongue or pen,

the saddest are “Prequel again?”

Mirrored from Ambrose & Elsewhere.

Of all sad words of tongue or pen,

the saddest are “Prequel again?”

Mirrored from Ambrose & Elsewhere.

I’ve been following with interest Steven Silver’s great series of reviews of the Tor Double books at the Black Gate. His latest, scrupulously fair, review of Brackett’s The Sword of Rhiannon+de Camp’s Divide and Conquer reminded me of one of my favorite Latin sayings: de gustibus non disputandum est. Or, in the words of a cinematic classic:

People get to like what they like and not like what they don’t like. Personally, I like The Sword of Rhiannon (a.k.a. Sea-Kings of Mars) a lot; it’s my favorite of Brackett’s sf/f novels. But I hadn’t reread it in a while, so I thought I’d see if I still found it good. (Spoilers: I did. Details and complications below.)

In the course of the reread, I thought of a much more effective pairing for Brackett’s novel: Zelazny’s Isle of the Dead. Both the Zelazny and the Brackett share the same conceit (men who overlap with gods), and they share some other weaknesses and strengths—so much so that I began to think that Isle of the Dead was at least partly inspired by and in response to The Sword of Rhiannon, something that had never occurred to me before.

First up: my thoughts about the older book, then the later, and finally some points of comparison.

Re titles: Brackett’s book first appeared as a “Complete Novel” in the pulpy pages of Thrilling Wonder Stories (June 1949), under the title Sea Kings of Mars. It appeared a few years later in an Ace double as The Sword of Rhiannon (backed with REH’s Conan the Conqueror), and later editions always carried the Sword of… title in Brackett’s lifetime, so we can assume that it was the author’s preferred title. Sea Kings of Mars has a Burroughsian clang to it, but the Sea Kings are secondary or even tertiary characters in Brackett’s book. Rhiannon and the man he haunts are at the center of the story.

The man in question is Matthew Carse. He’s an Earthman, but he’s spent most of his 35 years on Mars. He was trained as an archaeologist but (like Indiana Jones and Belloq) has “fallen from the purer faith” and is now a thief and a tombarolo. A weaselly Martian guy named Penkawr tracks him down in the mean streets of Jekkara, one of the most dangerous of the Low Canal towns of Mars.

Brackett’s Mars is one of her greatest creations: a desert planet laced with canals, in the spirit of Percival Lowell and ERB; a planet dying but not dead; a planet that suffers under the colonial power of Earth.

Penkawr needs Carse because of his skills as an archaeologist and a crook. The Martian has discovered an unbelievable find: the tomb of dark Rhiannon, villain-god of the ancient Quiru, lost for more than a million years. Penkawr knows that he can’t safely dispose of the tomb’s fabulous treasures, so he proposes a partnership to Carse. And he proves his claim by handing Carse the most fabulous of the aforesaid treasures: the sword of Rhiannon.

Carse agrees, insisting on a two-thirds share.

“<Penkawr> turned and fixed Carse with a sulky yellow stare. I found it,” he repeated. “I still don’t see why I should give you the lion’s share.”

“Because I’m the lion,” said Carse cheerfully.”

Penkawr: not so cheerful. When they get to the tomb of Rhiannon, he shows Carse a disturbing mysterious globe of darkness. While Carse, reverting to archaeologist mode, is rapt in wonder, Penkawr pushes him into the globe. The thief figures he can make a better split with a less leonine partner.

Carse, meanwhile, falls through space and time, haunted by a terrifying presence in the darkness. He comes to himself in the tomb of Rhiannon but now, as he swiftly realizes, it’s a million years in the past. Instead of a dying, desert world, Mars is a green world rich in lives and waters, being fought over by savage kingdoms, who have lost or never possessed most of the technology of the ancient, godlike Quiru.

Carse returns to a Jekkara a million years younger than the one he knew. In the older city, he was a respected member of the aristocracy of thieves. In this young, vibrant Jekkara he is instantly loathed because of his skin color. A mob attacks him because they believe he’s from Khondor, an alliance of piratical sea-kings with whom the Sarks and their subject cities (including Jekkara) are at war.

Carse is saved by a wily, fat rascal named Boghaz Hoi. This guy hails from Valkis and he has, as he says, “my own reasons for helping any man of Khond”. He’s also a thief and he recognizes the stuff Carse has as worth stealing. Once he examines it closer (having knocked Carse cold for the purpose) he realizes that they are relics of the sinister villain-god Rhiannon, already an ancient and mythical being in this much-younger Mars. When Carse comes to himself, Boghaz tries to persuade Carse to lead him to the tomb of Rhiannon, much as Carse persuaded Penkawr to do earlier in the story (and a million years later in history). But Carse is stubborner than Penkawr, and Boghaz too; they are still discussing the matter when they are arrested by the soldiers of Sark.

The Sarks put both Carse and Boghaz to work on one of their galleys, which is conveying Lady Yvain back to her tyrannical father, Garach, King of Sark. Scyld, the captain of the ship, claimed Carse’s valuables as his own, including the sword of Rhiannon, which Scyld does not recognize.

Is this the end of the story? Will Carse and Boghaz end their days chained to an oar in this slave-ship? Obviously not. But it’s a handy place for Carse to learn something about this world, so different from the Mars where he grew up.

For one thing, there are a number of nonhuman species in this world, the Halflings. The godlike, yet human, Quiru created Swimmers (amphibious pseudo-humans who can breathe under water), the Sky Folk (winged semihumans who can fly), and the snakelike Dhuvians, collectively known as the Serpent. Their distinguishing characteristics of the Dhuvians are high technology and evil.

Before the godlike Quiru left Mars, they imprisoned Rhiannon in his tomb as punishment for a terrible crime. The crime was lifting up the Dhuvians and gifting them with some portion of his scientific and technical knowledge. It is the Dhuvians who are the sinister power behind the empire of Sark, through which they hope to conquer and enslave the world.

Carse eventually comes to realize that, when he passed through the time portal in Rhiannon’s tomb, the villain-god attached his mind to Carse’s so that he could escape imprisonment in the black globe. Rhiannon periodically begs Carse to help him do something, but Carse rejects him—until he realizes that what Rhiannon wants is to destroy the Dhuvians, undoing the crime for which the Quiru imprisoned him.

Without going into spoiler-laden details, it suffices to say that Carse and Rhiannon, working alone or in tandem, succeed in destroying the Dhuvians, breaking the power of Sark, and freeing the subject cities like Valkis and Jekkara from the Sarks’ imperial dominion.

You practically can’t have a sword-and-planet story without a space princess. As someone once put it, the original template for the sword-and-planet story as defined by the Procrustean bed of ERB’s A Princess of Mars was: “a lone American (not a Canadian–not a Ugandan–not a Lithuanian–an American) is mysteriously plunged into an exotic other world which is both more advanced and more primitive than the earth he knows. He conquers all by virtue of his heroism and marries the space princess.”

Sword-and-planet became a more varied genre by the 1940s-1950s; Leigh Brackett herself helped to stretch the boundaries. But there is a space princess in this story, Yvain of Sark, and it’s not really a spoiler to let you know that Carse and her end up together despite some early antagonism. They end up fighting side-by-side against the Dhuvians. (That’s them on the cover of Thrilling Wonder Stories above.) Yvain is a likably tough and free-minded character, not just a storytelling cliché; she could easily be the protagonist of her own story.

In heroic fantasy, it’s not uncommon for the hero to kill the bad guy. In sf of the 1930s-1940s, the bad guy is frequently a nation. In heroic fantasy which is pretending to be science fiction (a decent quick-and-dirty definition of sword-and-planet), would the hero kill an entire nation or species?

Obviously not. Genocide is immoral, consequently not heroic. Right?

Right, but genocide is the happy ending of many a story in old-school space opera. Consider the Lensman series by E.E. “Doc” Smith, where it is frequently the task of the heroes to wipe out entire species, like the Overlords of Delgon, or the unspeakable Eich, or the shapeless amoral monsters of Eddore.

It’s Rhiannon, rather than Carse, who imposes the Final Solution on the Dhuvians, so one could argue that Carse is not responsible. But it’s Carse and the other protagonists who benefit. All faves are problematic faves, as we know (or used to). This is the most problematic element in this fave for me. It works in the universe of the novel because the Dhuvians are established to be 100% bad. In the real world, that’s a racist idea that should never pass by without being challenged.

A less serious problem—maybe not a problem at all—are the naming conventions. If you know anything about Welsh myth or Arthurian legend, you’ll be surprised to find Rhiannon a man (or a male, anyway) and Yvain a woman. Then there’s Scyld—but a book could be written, maybe should be written, about names in heroic fantasy. For the time being, when confusion arises, I recommend banishing it by chanting the wise words of an ancient song:

“repeat to yourself it’s just a show; I should really just relax.”

Boghoz Hoi is worth a mention before I move on, too. He’s a worthy addition to the long tradition of cowardly, selfish, semiheroic sidekicks going back to Falstaff, at least, and including space opera characters like Giles Habibula from Williamson’s The Legion of Space.

Another thing that cries out for mention when discussing Leigh Brackett is her absolute mastery of style. This doesn’t matter to some readers; the text is just a screen through which they see the story. They don’t hear or see the shape of the words. But for those that do, reading Brackett is like listening to music.

Here’s the moment when Penkawr shows Carse the sword of Rhiannon:

The thing lay bright and burning between them and neither man stirred nor seemed even to breathe. The red glow of the lamp painted their faces, lean bone above iron shadows, and the eyes of Matthew Carse were the eyes of a man who looks upon a miracle.

You either like this sort of thing or you don’t. If you like it, you will like this book a lot.

As noted above, the Tor Double paired Brackett’s short novel with another by de Camp, but a better match (it seems to me) would have been Zelazny’s Isle of the Dead (Ace, 1969).

Isle of the Dead is a multi-media experience. There’s the original paintings (sic: multiple versions) by Böcklin. (See above.) Then there’s Rachmaninov’s tone-poem inspired by the painting.

There’s a pretty good Val Lewton film, starring Boris Karloff, that makes use of the same setting. The monster in this film is a real one, and very timely: a crazy person who forces people to live and die in accordance with his demented ideas. Boris Karloff plays the RFK jr. role in this classic.

Last and (honesty compels me to admit) least there is Zelazny’s Isle of the Dead, a heroic fantasy pretending to be science fiction.

Is Isle of the Dead sword-and-planet? The way I just described it may imply “yes”. Others might say “no”.

This is, one might argue, a pretty standard science-fiction novel by the standards of the 1960s, featuring a high-technology culture with frequent space travel. How could a science fiction novel with realistic technology like FTL ships, laser weapons implanted in fingertips, and resurrection technology possibly qualify as a kind of fantasy?

Well: remember that not-exactly-serious definition from above: “a lone American (not a Canadian–not a Ugandan–not a Lithuanian–an American) is mysteriously plunged into an exotic other world which is both more advanced and more primitive than the earth he knows. He conquers all by virtue of his heroism and marries the space princess.”

The hero is an American from the late 2oth century. He is plunged into an exotic future world by a series of STL interstellar voyages, during which he is in suspended animation. He finds himself in a universe which is more advanced than the one he came from (the aforesaid FTL ships etc), but also more primitive: the most advanced people in the galaxy, the Pei’ans, live in a low-tech environment, engage in something very like magic, and practice an ethos dedicated to elaborate revenge. There’s even a space princess in the story, who the hero ends up with. So maybe this story is sword-and-planet, or at least adjacent to it

The hero, Francis Sandow, learns the wisdom of this ancient race and becomes a Dra—both a priest in the ancient Strantri religion, and a worldmaker—someone who can use tremendous technological and personal forces to reshape worlds. This is a godlike power, and each Dra is associated with one of the countless gods of the Strantri religion in a mystic ceremony where the would-be Dra and the god become entangled with each other.

Sandow is a reasonable person, even and you and I are, and he doesn’t believe this nonsense for a moment. The stuff about being a god is just metaphorical: “It is a necessary psychological device to release unconscious potentials which are required to perform certain phases of the work <of worldbuilding>. One has to be able to feel like a god to act like one.” As far as Sandow is concerned, Shimbo, Shrugger of Thunders, whose image lit up when Sandow passed it during the confirmation ceremony, is just a figment of his imagination—a mask he wears, a tool of his trade, not a god.

Maybe so. But others feel differently. Shimbo has an ancient enemy among the gods: Belion the Destroyer. Gringrin Tharl, a Pei’an fundamentalist, who resents the revisionist attitude of Sandow and the other worldmakers, undergoes the confirmation ritual and becomes identified with Belion. Then Gringrin (or Belion) launches on a centuries-long quest for revenge against Sandow, who doesn’t even know he exists. This climaxes when Gringrin (or Belion) kidnaps a half-dozen of Sandow’s friends, lovers, and enemies, both living and dead, and challenges Sandow to come and get them from the Isle of the Dead.

This not being a fantasy novel (unless it secretly is), the Isle of the Dead is located on a world named Illyria which Sandow himself created on commission centuries before. Gringrin/Belion acquired it and has been corrupting it as part of his/their revenge against Sandow/Shimbo.

In the end, Sandow has to go alone, on foot, to the river Acheron and the Isle of the Dead to confront his enemy, who is wearing a face he will not expect.

This is the summary of a ripping yarn, in my view. Does Zelazny actually deliver one?

Well, yes and no. Zelazny has to get his hero from a mundane world to a magical one (cf Nine Princes in Amber, where Corwin wakes up in a 20th-century hospital suffering from amnesia and has to grope his way into the magical world he senses but does not understand or remember). From my point of view, this is hampered by the fact that Sandow, at the story’s beginning, is kind of an unlikable character, rich and crassly materialistic “eating fancy meals <and> spending my nights with contract courtesans” as he himself puts it.

Once he gets jolted into motion, the story works a little better for me. There is a long detour to justify the idea that Gringrin could scientifically resurrect the dead from Sandow’s past and be holding them prisoner in the narrative now. I found this somewhat tedious, and no more convincing than if a sorcerer waved a wand to get the same result. But this is the kind of narrative furniture that you stumble over when you’re dealing with one of these heroic fantasies disguised as sf.

It’s when Sandow lands on Illyria and begins walking toward the Isle of the Dead that the story really begins to fulfill its promise. Sandow considers the gods to be convenient fictions, made for the benefit of mortals. The gods themselves have different ideas, and bring the situation to mortal conflict in conflict with the wishes of the mortals involved. But, in the end, it is Sandow, not Shimbo, who strikes the deciding blow and emerges, still-breathing if badly wounded, from the final confrontation.

So: good things and bad things here. Good things include some vivid characters (especially Nick the dwarf, who blazes like a comet through the second half of the book, and the would-be Dra Gringrin Tharl who acts as both enemy and sidekick to Sandow), and some entertaining Raymond-Chandler-in-space passages filtered to us through Sandow’s narrative persona.

On the down side: Zelazny, like Brackett, was one of the great stylists of 20th-Century sf/f, but he’s not working at the top of his game here. De gustibus, etc, but I don’t find his descriptions of the Isle of the Dead anywhere near as evocative as the paintings, the music, or even the movie focused on the same scene. Zelazny also displays his willingness to go for the cheap laugh, at the expense of more important values. The planet Illyria has three hurtling moons, similar to but different from Barsoom’s. They are called Flopsus, Mopsus, and Kattontallus—Flopsy, Mopsy, and Cottontail. I can see Zelazny smiling to himself as he typed these names out, but they disrupt the heroic scene that Zelazny is setting. And the last scene of the book includes the most unforgivable line in the Zelazny canon: “Forgive me my trespasses, baby.” Urgh.

Also: Zelazny’s women tend to be malicious, to the extent that they’re not passive, and this novel is more evidence of that. Some women are passive, of course, and others are malicious. It’s the regularity with which these tropes appear in Zelazny that makes my teeth grate. In this way, Zelazny is somewhat less modern than his older contemporary, Brackett.

One of the things that makes me think that Zelazny is riffing on, or replying to, Brackett’s novel is that genocide comes up a couple of times. One doesn’t hear Zelazny murmuring, “Never again”, but at least the act is problematized in a couple ways.

Another is, as I mentioned above, the central conceit of both books, where a man acts (willingly and unwillingly) as the vehicle of a god. In both books, the man and god struggle for control. In both books, the final end is achieved only when the man and god can bring themselves to work in tandem.

And both are heroic fantasies with a candy-coating of super-science—magic, by Clarke’s Third Law.

I don’t seem to have any great thumping conclusion to put here, but maybe my patient readers feel like they’ve been thumped enough.

In summary, these works of heroic fantasy have some flaws, but remain worth reading. Forgive them their trespasses. Maybe someday someone will do the same for you.

Mirrored from Ambrose & Elsewhere.

The Surprised Eel on their Patreon gives us a very nice piece of writing that usefully complicates some over-simplified worldmaking advice.

One thing that leapt out at me was this:

“Of course, your fantasy world doesn’t have to work like the real world, but most people’s fantasy realms operate with the same basic rules of physics as our own.”

Both parts of this statement are true, but I’m not convinced the second part ought to be true.

Fantasists are missing a bet if they unthinkingly accept the restrictions of our reality for their invented reality. If your Elfland is just like Poughkeepsie, you might as well set your story in Poughkeepsie.

If it’s not like Poughkeepsie, you have the liberty of saying “Water runs uphill in Vrandobogia” or “The river divides here because the twin daughters of the River Vrand had a quarrel” etc.

Scientists & historians must have fidelity to facts. Fantasists must have fidelity only to our dreams.

[ETA:

TL;DR version: In fantasy worldmaking, the impossible is not only possible; it is desirable.]

Mirrored from Ambrose & Elsewhere.

Not trying to subtweet anyone, particularly my students, whose papers I’m wading my way through. But I’ve had a lot of occasion today to think about the identification of “great” with “first/inventor”. If some creator/creation is a a great example of something, and maybe the most famous example of a thing, there is a tendency to treat them/it as the first instance of the thing.

e.g.

“Bozo invented the tradition of modern clowning, setting the stage for the great clowns of the late-20th century, like Crusty and It.”

This seems like it’s just a compliment to Bozo. But it actually erases earlier, maybe even more important clowns like Emmett Kelly. Celebration of Y shouldn’t cause the erasure of X.

Not sure where the source of the first=best error lies. It could be from sports culture, where the second person across the finish line is nowhere near as glorious as the first. Or maybe it’s from science/technology, where the second guy to split the atom is not the guy who gets the Nobel Prize.

Those standards are not wrong, but they’re typically not going to apply to the arts. Think of all the misconceived arguments about who “invented” science fiction, as if it were the telephone or the radio.

The opposite error is the myth of progress–that later=better. So novels published in 2025 are marginally better than those published in late 2024, but not as good as those that will appear in 2026. That tendency may be true of computer hardware, but is never going to be true of writing, music, the visual arts, etc.

A still greater error is spending endless hours on social media rather than doing work that has to be done, in the vain hope that elves will come along and do it for me. That’s a mistake.

OR IS IT

Mirrored from Ambrose & Elsewhere.

Much of the short paragraph below by Fredric Brown is outdated and/or not meant to be taken seriously. But I like his conclusion about sf, which I would broaden to include fantasy (as sf often did in those now-distant days: note the dragon wrapped around the spaceship in the image).

“It is a nightmare and a dream. And isn’t that what we’re living in and for today? A nightmare and a dream?”

Mirrored from Ambrose & Elsewhere.

When I heard about G20 (directed by Patricia Riggen), an action movie set at the titular summit in which Viola Davis plays an American president in action-hero mode, I knew I would have to watch it. I figured it would be dumb fun. And I was right, and I was wrong. It was mostly fun, but mostly not dumb.

Spoilers follow.

If you are looking for a movie where serious problems are addressed without violence, this is not that movie. But it’s not as empty of significance as action movies generally are.

The worst part is the opening, which features an unlikely McGuffin carried by a woman (Angela Sarafyan) who’s being chased by sinister agents, while elsewhere the president of the United States is aroused from well-earned slumber by an aide telling her that a code-named subject has been retrieved.

What’s wrong with that? The McGuffin is an electronic wallet for some kind of cryptocoin. I figured I was going to have to sit through a commercial for the blockchain. Blecch.

Plus: the scenes in the White House had nothing to do with the suspense plot. The code-named target was the president’s teen-aged daughter (Marsai Martin) who had evaded surveillance and snuck off to a bar. She’s mad that she was dragged back by the Secret Service and she’s mad at her mom. This is great, because surly teenage daughters are so rare on screen these days that—no, just kidding, they are apparently essential to modern storytelling.

I’m sure there are surly teenage daughters in this world, just as I am sure that most friction between teenagers and parents comes from the parents being various kinds of jerk. Don’t bother to argue with me about this. I’m old and I never change my mind about something unless I’m wrong, which I’m not in this instance. In any case, it’s an incredibly trite narrative move. Blecch again.

“Is this movie going to bore me?” I asked Dr. Reuben Sandwich, my sole companion on this adventure (since D was off rehearsing a play). He did not immediately answer.

Anyway, I figured three blecchs and they’re out: I’d turn the movie off.

But, in fact, the movie did not turn out to be some credulous puff-piece for crypto, and although the teenage daughter is introduced in the most stupidly cliche way possible, her escape from surveillance turns out to be a plot-relevant skill, and when the plot gets underway she acts in a commendably reasonable manner.

In fact, that’s true of most of the characters in the movie, and is one of the best things about it. Everyone in it acts with reasonable intelligence in pursuit of what they see as their own interests. This is not an idiot plot. That might seem like faint praise but it’s not. Useful idiots abound in storytelling (and politics, too, but let’s try to avoid thinking about that).

The suspense plot involves a group of criminals, deeply embedded into U.S. security services, taking over the G20 summit. The goal is to crash the world economy, causing cryptocoin prices to soar, enriching the criminals. They’re not exactly terrorists but their leader (capably played by Antony Starr) has a political axe to grind which sounds a lot like Brexit/MAGA gibberish. But the money is the main thing for them, like the gang in Die Hard, the illustrious ancestor of this type of movie.

When the criminals attack, the ex-military US President escapes, taking with her the doltish, yammering UK Prime Minister (Douglas Hodge), the head of the IMF (Sabrina Impacciatore) and the First Lady of Korea (MeeWha Alana Lee), all of whom are watched over by the president’s principal Secret Service guard (Ramón Rodríguez)—until he takes a disabling bullet. At that point the president herself has to take the lead, risking life and limb to save her accidental companions, her family, and indeed the world.

I won’t go into the gory details, except that it does get a little gory. No more than the average James Bond movie, but that would include a pretty high body count. If you like this kind of movie, this is the kind of movie that you’ll like.

There is a significant political message here, which probably won’t bother you if you’re not crazy. The reviewer at RogerEbert.com found some of this stuff “too on-the -nose”. Personally, as a guy watching a lot of old WWII movies because the news is so frustratingly deranged, I didn’t have a problem with the messagey parts. There is a time and place for that kind of stuff; the time is now and the place is here, until things get considerably better than they are.

The political philosophy isn’t just a candy-coating. It’s woven through the work. There is considerable personal heroism in this movie, but it’s given meaning and effectiveness by intelligent cooperation with other people. And whenever anyone in the plot gets so full of themselves that they’re not prepared to take a clue, one is forcibly delivered.

A good example is when the president and her guard are standing around arguing about how they’re going to go through a door with some armed bad guys on the other side. The head of the IMF and the UK Prime Minister are bickering about something else. Meanwhile the SK First Lady has an idea for an alternate route: down the laundry chute. No one will listen to her (because no one listens to old ladies, even when they notice they’re there) so she shrugs and dives down the laundry chute. At that point, every realizes that there is a way out that doesn’t involve getting shot at and they follow her down.

By the time we get to the scenes where the president is kicking and shooting her way through villain-rich environments like one of the badass heroes from Person of Interest, it’s almost believable, since Viola Davis (and the script) have done so much good work humanizing the character. Anyway, by that time you’re rooting for her. (When I say you I mean me, really; de gustibus, and all that.) But it’s her shrewdness and observational skills that let her figure out Who Is Really Behind It All.

Watching this movie was a painfully melancholy, almost nostalgic experience in a way almost certainly not intended by its makers. It’s set in an alternate timeline where the US has a capable leader and the nation itself is still a respected leader in world affairs. But that was long ago—five or six months, at least. It’s amazing how far and how fast a nation can fall when it falls from a height.

Anyway.

In summary: the movie might be a half hour too long, as almost every movie is these days, and some of the more obviously CGIed scenery looks a little thin. But in general this is a fast-paced, intelligent action movie with a solid soundtrack and fine performances from a diverse cast.

P.S.

Re the soundtrack: this was my favorite track, by Miriam Makeba.

Mirrored from Ambrose & Elsewhere.

It’s been sometimes sad, sometimes joyous, but always a pleasure to hang out with people at Windy City Pulp and Paper and celebrate the life and work of Howard Andrew Jones.

Too many stories were shared for me to scribble down. But the common theme was: Howard’s deep interest in people and his intense empathy were central to what made him a great editor, a great writer, and a great human being. “If you knew Howard, he was your friend.” I forget who in the sizeable audience said that (Bob Byrne, maybe?) but it echoed with agreement around the room.

Hocking has sometimes said about storytelling, “Action is character,” and it’s become one of my mantras for writing. But, as he pointed out last night, Howard’s character, his belief in decency and heroism, was key to his work and his life.

It was S.C. Lindberg who found the closing words for the panel. They were Howard’s words, the way he closed countless letters and conversations.

”Swords togther!”

Mirrored from Ambrose & Elsewhere.

For various reasons I’ve had a couple different essays under my eyes this afternoon: “Epic Pooh” (Moorcock’s Titanic body-slam against Tolkien and other “high” fantasists) and Tolkien’s “On Fairy-Stories”.

All critical writing about fantasy needs to be taken with a pinch of salt. When the critics are themselves fantasists, you’d better have pounds of the stuff on hand. I’ve noted this before about Le Guin. She is, to my mind, the greatest stylist among modern fantasists. Her essay on style and fantasy, “From Elfland to Poughkeepsie”, is a must read. But, as I’ve argued elsewhere, she’s not infallible.

Clarke’s First Law is the relevant standard to apply here.

When a distinguished but elderly scientist states that something is possible, he is almost certainly right. When he states that something is impossible, he is very probably wrong.

Replace “scientist” with “critic”/“scholar”/‘artist”/“writer” and you’ve got it. (Also be aware that in the now-distant day when Clarke was writing, “he” could be used of people in general, regardless of their natural gender, because personhood was gendered masculine. I don’t endorse this position; I just report it.)

Moorcock’s discussion of Tolkien (and the style of much high fantasy) is worth reading, whether you agree with it or not.

The sort of prose most often identified with “high” fantasy is the prose of the nursery-room. It is a lullaby; it is meant to soothe and console. It is mouth-music. It is frequently enjoyed not for its tensions but for its lack of tensions. It coddles; it makes friends with you; it tells you comforting lies. It is soft.

He doesn’t like it.

And I guess I get that, especially given the date of Moorcock’s original essay, a time when bookstands were groaning under the weight of Tolkienian knockoffs. If Moorcock is less than fair to Tolkien, he’s certainly got the number of the Tolkienizers.

I would argue, though, that Tolkien himself has more than one string to his epic harp, and in particular when he’s writing about war (something that he, unlike most writers of heroic fantasy, experienced at its worst) we see him in a different mode.

Here’s Pippin in battle at the Black Gate of Mordor:

Like a storm <the orcs> broke upon the line of the men of Gondor, and beat upon helm and head, and arm and shield, as smiths hewing the hot bending iron. At Pippin’s side Beregond was stunned and overborne, and he fell; and the great troll-chief that smote him down bent over him, reaching out a clutching claw; for these fell creatures would bite the throats of those that they threw down.

Then Pippin stabbed upwards, and the written blade of Westernesse pierced through the hide and went deep into the vitals of the troll, and his black blood came gushing out. He toppled forward and came crashing down like a falling rock, burying those beneath him. Blackness and stench and crushing pain came upon Pippin, and his mind fell away into a great darkness.

’So it ends as I guessed it would,’ his thought said, even as it fluttered away; and it laughed a little within him ere it fled, almost gay it seemed to be casting off at last all doubt and care and fear.

Pippin isn’t actually dying; he just thinks he is. But it’s not a coincidence that Tolkien sends his most childlike characters (Pippin, Merry, Sam) into the most terrible places. Tolkien had been one of those children. As Tolkien remarks grimly and memorably, “By 1918 all but one of my close friends were dead.”

Moorcock is philosophically opposed to consolation, which for Tolkien is a major feature of fantastic storytelling. These are both legitimate points of view. But I would deny that Tolkien turns his eye away from grief and suffering and loss—the things people need consolation for.

Should people suffering from such things (and that’s everyone who lives, sooner or later) be offered any kind of consolation?

Absolutely not. Let them toughen up! Whatever it is, there’s worse coming.

Or maybe: No. It’s insolence and cowardice to babble chipper advice to someone suffering from terrible grief and pain.

Or maybe yes. If you think you can fairly offer it, if someone needs it, if it will do any damn good in a world without enough good in it, then maybe yes.

It’s not a question with just one correct answer. But as I get older, and fatter, and more corrupt, and as the world grows worse and worse, I have more and more sympathy for people who just want escape: for an hour, for longer, forever.

It’s not crazy for people who seek that kind of consolation to look for it in fantasy. And it’s not dishonest or corrupt for fantasists to try and offer it.

But with style, definitely. There’s a great line in Stan Freberg’s The United States States of America. A square general is asking a hipster fife player, “Do you want the war to end on a note of triumph or disaster?” And the fife player says, “Either way, man, just so it swings.”

That’s the only real rule for style. Either it works as verbal music or it doesn’t.

Mirrored from Ambrose & Elsewhere.

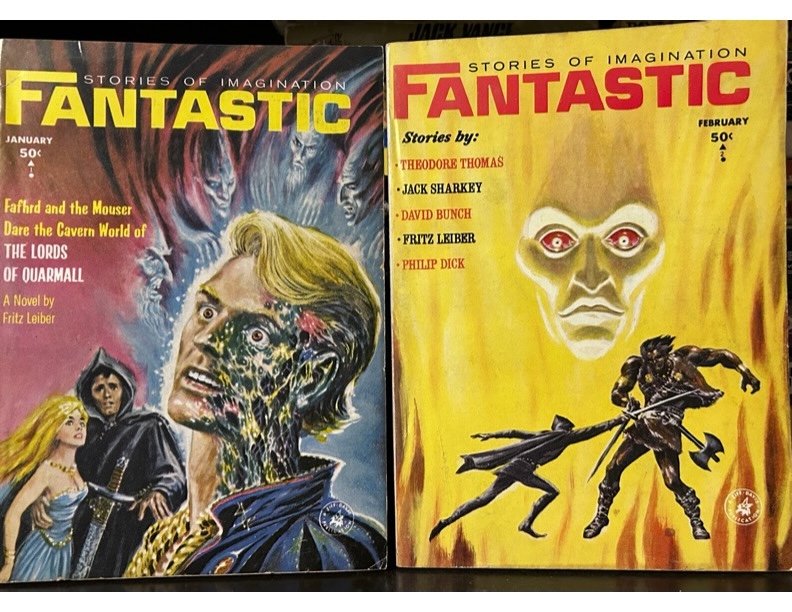

A couple years ago I set out to review all of Fritz Leiber’s books about Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser—foundational texts for sword-and-sorcery and for my personal imagination. I knocked off the first three (or four, depending on how you count) pretty quickly. (See my review of Swords and Deviltry here, my writeup of Swords Against Death and Two Sought Adventure here, and my misty water-colored memories of Swords in the Mist here.) Then I ground to a halt.

Why? In a single word: Quarmall. “The Lords of Quarmall” is not the least interesting of the stories about Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser, but it is by a fairly long chalk my least favorite, one that I almost always skip in rereading the saga, and it occupies roughly half the space in Swords Against Wizardry, the fourth volume in the Ace series collecting all the stories of the Mighty Twain. (I’m sure there are those that love the story. De gustibus non disputandum.)

But “The merit of an action is in finishing it to the end,” as Genghis Khan remarks, so here goes.

Is this book a novel? I’ve flogged that dead horse enough, possibly, so I’ll just say that the answer is absolutely yes. Or maybe no.

Anyway, the lion’s share of SaW‘s words belong to two unequal-sized novellas, “Stardock” and the aforesaid “Lords of Quarmall”, supplemented by an introductory episode, “In the Witch’s Tent”, and an interlude in Lankhmar, “The Two Best Thieves” in Lankhmar”. We’ll tackle them in the order that God and Leiber intended, but for once there’s no complicated backstory to the—no, of course there is, this being a Leiber book. But don’t worry about it. You’ve seen worse already.

I. “In the Witch’s Tent”

We find the Mighty Twain in the deep north, far out of the Mouser’s comfort zone. They’re in quest of a stash of legendary jewels said to be atop Stardock, the tallest mountain in their world of Nehwon. They stop in Illik-Ving, last and least of the Eight Cities, to consult a witch about their journey. While that’s happening they’re attacked by rivals on their quest, and take an unconventional route to escape.

This is just an episode, acting as an introduction to “Stardock” and written years later than the longer story. (It first appeared in SaW in 1968, whereas “Stardock” was first published in Fantastic three years earlier.)

But I like it a lot. It’s got some great back-and-forth between the heroes; the story, such as it is, moves swiftly, and there’s rich, disturbing detail about the witch and her tent.

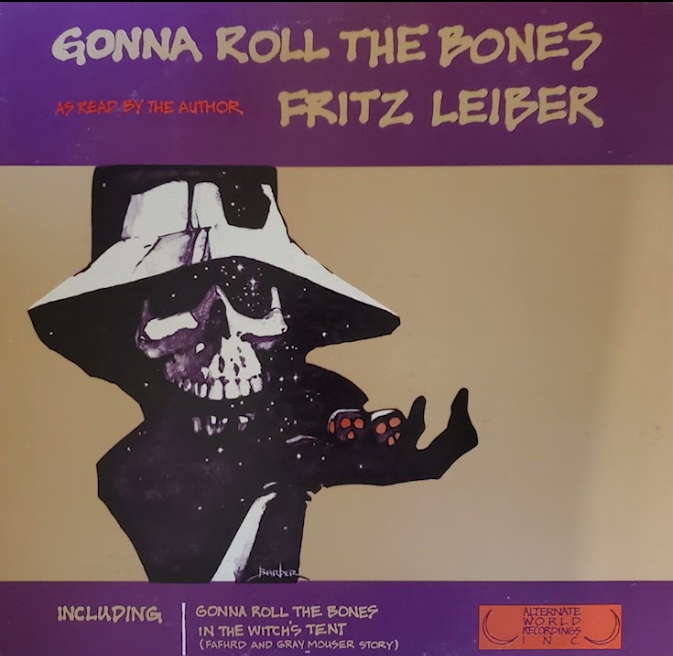

Plus, there’s a kind of audiobook. In the 1970s, there was a company named Alternate World Recordings that released LPs of great sf/f readers reading their stories. The best one, in my view, was Ellison’s “Repent Harlequin,” Said the Ticktockman. It’s not only a great story, but Ellison was a professional performer at the height of his powers. I also had, at one time, Theodore Sturgeon’s recording of Bianca’s Hands, and a couple others, among them Leiber’s reading of his mythic fantasy Gonna Roll the Bones. There was some space on the B-side of the LP (ask your grandparents, kids, or your hipster friends), so they added a recording of Leiber reading “In the Witch’s Tent.“

Leiber had briefly been a professional actor in his even-then-distant youth, but he didn’t stick with it and had lived a pretty hard life of alcohol and drug abuse. His voice is wavery in the recording. But he reads skillfully and with zest. I wish we had more of his voice.

A technical issue about the writing. Le Guin, who was the greatest stylist in American fantasy, wrote a great essay about style in fantasy, “From Elfland to Poughkeepsie”. In it, she took aim at two giants of sword-and-sorcery.

Fritz Leiber and Roger Zelazny have both written in the comic-heroic vein…: they alternate the two styles. When humor is intended the characters talk colloquial American English, or even slang, and at earnest moments they revert to old formal usages. Readers indifferent to language do not mind this, but for others the strain is too great. I am one of these latter. I am jerked back and forth between Elfland and Poughkeepsie; the characters lose coherence in my mind, and I lose confidence in them. It is strange, because both Leiber and Zelazny are skillful and highly imaginative writers, and it is perfectly clear that Leiber, profoundly acquainted with Shakespeare and practiced in a very broad range of techniques, could maintain any tone with eloquence and grace. Sometimes I wonder if these two writers underestimate their own talents, if they lack confidence in themselves.

I think Le Guin’s mistaken here, partly because she may underestimate the power and poetic impact of colloquial American English. Leiber knew exactly what he was doing in exchanges like the one below, and the literature of fantasy would be poorer without them.

“Shh, Mouser, you’ll break her trance.”

“Trance?” … The little man sneered his upper lip and shook his head.

His hands shook a little too, but he hid that. “No, she’s only stoned out of her skull, I’d say,” he commented judiciously. “You shouldn’t have given her so much poppy gum.”

“But that’s the entire intent of trance,” the big man protested. “To lash, stone, and otherwise drive the spirit out of the skull and whip it up mystic mountains, so that from their peaks it can spy out the lands of past and future, and mayhaps other-world.”

The clash of symbols between the Mouser and Fafhrd here is audible and intentional. The Mouser uses “stoned out of her skull” in one way, and Fafhrd understands it in another, investing the trite slang with mystic import. That’s not lack of confidence on the writer’s part; that’s complete understanding of the instrument he’s making music with.

II. “Stardock”

Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser arrive at a range of mountains in the Cold Waste, along with a snow-cat (a kind of lioness of the north) named Hrissa. Their task is to climb Stardock, but if climbing an unclimbable mountain weren’t enough of a challenge, they face human rivals with both weather-magic and werebear servants at their command, not to mention invisible enemies riding invisible flying bird-fish through the snows, and the occasional hotblooded furry snake-monster.

The clues to Stardock’s treasure were scattered around the world by the mountain’s savage yet sorcerous ruler, who’s looking for new seed to infuse into his people’s thinning bloodline. Fafhrd and the Mouser conquer the mountain despite all, sleep with a couple of invisible princesses, escape the more brutal attempts to collect their seed, and make it safely back to the base of the mountain, which is more than their rivals can say.

The ascent of Stardock is one of the great mountain-climbs in fantasy fiction, matched only by Juss and Brandoch Daha’s ascent of Koshtra Pivrarcha in the mighty Worm. It’s harrowing and dense with authentic detail. Leiber mentions in “Fafhrd and Me” how he climbed the occasional rock himself, and he dedicates “Stardock” to Poul Anderson and Paul Turner “those two hardy cragsmen”. No doubt they swapped a few stories.

A must-read for the sword-and-sorcery fan.

III. “The Two Best Thieves in Lankhmar”

The Mouser and Fafhrd have fallen out on the long road back to Lankhmar. They split the loot and take different paths to fence their valuable but hard-to-dispose-of jewels from Stardock. Their different paths bring them to the same place at the same time: the intersection of Silver Street with the Street of the Gods in early evening. There the aristocracy of Lankhmar’s thieves are gathered, and the Twain grudgingly admit to each other that they’re the best of the lot.

Or are they? Before the end of the night they’re shorn like sheep and heading out of town by different routes.

This is just a transitional piece, to link “Stardock” with “The Lords of Quarmall”, but it’s nicely done. There’s some nice writing, and some nifty worldbuilding touches for the city of Lankhmar; we get a first mention of Hisvin the merchant, who’ll figure largely in The Swords of Lankhmar, and we see a lot of the thieves of the City of the Black Toga, including one intruder from another world: Alyx the Picklock, heroine of a wonderfully weird set of stories by Joanna Russ. Russ borrowed Fafhrd for her first story about Alyx (“The Adventuress”, a.k.a. “Bluestocking”), and this is Leiber nodding back at her.

IV. “The Lords of Quarmall”

Okay. Here we are. What’s not to like about this novella?

There’s a lot to like about it, that’s for sure. For one thing, it includes the only substantial writing in the saga from Harry Otto Fischer, who invented Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser in correspondence with Fritz Leiber in the 1930s. He’d written about 10,000 words of a story and ground to a halt. With his approval, Leiber took his draft and wrote 20,000 more words, fitting in sections from Fischer as he did so.

In the novella, Fafhrd and the Mouser both find themselves in the subterranean realm of Quarmall as it comes on a crisis of succession in power. The current Lord of Quarmall is about to die, setting up a battle between his two sinister sons: sadistic, twisted Hasjarl and kindly, murderous Gwaay. Unbeknownst to each other, Fafhrd has gone into the employ of Hasjarl and the Mouser has been hired by Gwaay.

One of the two sons has to win the coming battle, and that means that their two bodyguards must come into mortal conflict. Unless there’s some third way for things to go. (Spoilers: there is.)

An interesting setup, certainly, and there are some good things along the way.

However, I find the pacing in this story to be off. For instance, the first 10 pages of the novella are just the Gray Mouser and Fafhrd each being bored in their respective places in Quarmall. Boredom is a difficult subject for fiction: it’s hard to depict it without boring the reader, and there’s seldom any point in doing it. Doubling these scenes by having Fafhrd and the Mouser go through almost exactly the same discontents doesn’t make it more interesting. Boredom in stereo is still boring.

Things start to pick up when the sorcerous stalemate between the two awful brothers breaks down. That’s forty-five pages into the story, but better late than never. In the end, Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser will face each other in battle, like Balin and Balan in Malory’s Morte d’Arthur, but less tragically, while Hasjarl and Gwaay settle their sibling rivalry in the only way that can satisfy them both, and the next Lord of Quarmall reveals himself.

It’d be interesting to figure out which parts of the stories are Fischer’s and which are Leiber’s. I spotted a couple passages I think may have been written by HOF rather than FL. One is the long infodump in the form of a letter sent to Fafhrd from Ningauble. It’s well-written but doesn’t sound like Leiber’s Ningauble; it’s interesting and shows great elements of worldbuilding, but it doesn’t advance the story at all–and in fact is slightly in conflict with it. Another is a scene where a local farmer narrowly escapes being captured by the Quarmallians. Again, it’s well-written and interesting, but doesn’t advance the plot. There are a few other bits that stand out to me. But unless there’s some evidence in the Leiber papers, wherever they are kept, I doubt we’ll ever know about this.

Not a worthless story, anyway; Leiber was incapable of writing something that is not worth reading. But the end of it has Fafhrd and the Mouser racing back to Lankhmar, where a far better tale awaits them in The Swords of Lankhmar.

Mirrored from Ambrose & Elsewhere.

I’m not a big fan of literary criticism in any field (although I have committed some), but one of my big books from my late teens onward was Le Guin’s The Language of the Night (1979), especially for the essays “From Elfland to Poughkeepsie” and “A Citizen of Mondath”.

Le Guin has some great passages in “Citizen” about what she liked to read as a kid, and how she liked it.

We kids read science fiction in the early forties: Thrilling Wonder, and Astounding in that giant format it had for a while, and so on. I liked “Lewis Padgett” best, and looked for his stories, but we looked for the trashiest magazines, mostly, because we liked trash. I recall one story that began “In the beginning was the Bird.” We really dug that bird. And the closing line from another (or the same?)—“Back to the saurian ooze from whence it sprung!” Karl made that into a useful chant: The saurian ooze from which it sprung / Unwept, unhonor’d, and unsung. I wonder how many hack writers who think they are writing down to “naive kids” and “teenagers” realize the kind of pleasure they sometimes give their readers. If they did, they would sink back into the saurian ooze from whence they sprung.

I’m pretty sure the first story she refers to is “The Unpleasant Profession of Jonathan Hoag” by Heinlein in Unknown (Oct 1942). It appeared under the false whiskers of “John Riverside” because at the time the Heinlein byline was reserved by John W. Campbell for RAH’s “future history” stories.

I never figured I’d find the source of the mysterious “saurian ooze”–except that maybe I just did. In looking for Henry Kuttner stories online I found this opus in Strange Tales (Aug, 1939). The appearance is pseudonymous, because he had a “Prince Raynor” novelette in the issue under his own name. And the crucial phrase was from the editorial blurb rather than the story itself.

Kuttner, of course, was roughly half of “Lewis Padgett”, along with C.L. Moore. And most of their work, whatever name it appeared under, seems to have been collaborative from the time they met and married, so Moore may have exuded some of that saurian ooze herself.

Le Guin’s accounts don’t exactly match up with these texts: “In the Beginning was the Bird” is a ritual phrase used by the Sons of the Bird in Heinlein’s story (one of his best fantasies, by the way), but it’s not the opener of the story. And the saurian ooze springs out at the reader at the Kuttner story’s beginning, not its end (and with a shift of ablaut at that). But given that Le Guin was writing about these stories 20-30 years after she’d read them, I’d say the shoes fit the footnotes pretty well.

Mirrored from Ambrose & Elsewhere.

I’m rereading Beowulf, preparatory to teaching it in a couple weeks to my Norse Myth class. This kind of thing always involves falling into the dictionary and getting swept away by a tide of weird words.

This afternoon’s discovery is morðcrundel. Morð means “death”; it’s the root of murder and Mordor (a linguistic fact that Asimov used in one of his stories of the Black Widowers), and is cognate with Latin mors, mortis “death”. (It occurs to me that this probably affects the spelling of Mordred’s name in Arthurian legend. The older spelling is Medraut/Modred, but it was changed in the Old French versions, maybe because storytellers associated Mordred with death and destruction—of his uncle-father Arthur in particular.)

Crundel (to my ear) sounds too friendly to be linked up with doomful morð, but Clark Hall & Merrit say it means “ravine”. (None of my dictionaries gave me an etymology for crundel, but I wonder if it’s cognate somehow with ground.) Hence morðcrundel “death-ravine”: the pit under a barrow where the dead are buried.

I expect morðcrundel (the word) and death-ravines (the phenomenon) will appear in my stories in the near future.

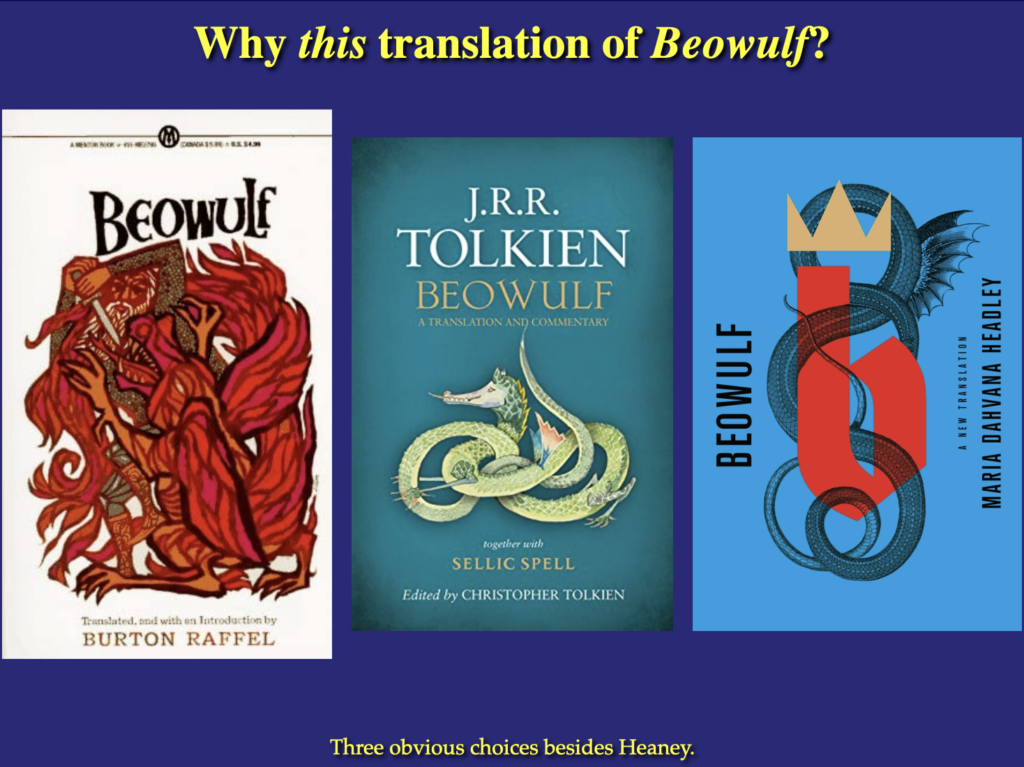

I’m reading Beowulf in stereo this time, comparing the Old English original to Heaney’s translation (which is the one I’ve been assigning to my classes for the past few years).

There’s no translation like no translation. Or, as they say in Italian: traduttore, traditore (“translator = traitor”). This kind of passage-by-passage comparison is the kind of reading that is most likely to make one unhappy with almost any translation. Heaney’s translation is clear and eloquent, a good match for the modern reader. They didn’t give this guy the Nobel Prize for nothing.

But in a couple passages he munges the meaning of things that (to my fantasy-oriented mind) are important.

One of the praise-songs about Beowulf in the text of Beowulf is about Sigmund the Dragonslayer. I particularly want to bring this passage to the attention of my students, because we’re also going to be reading the Volsunga Saga and the Eddic poetry about the screwed-up family of the Volsungs (and the screwed-up families they become entangled with). In those better-known versions, it’s Sigurð, son of Sigmund, who kills the dragon.

“Myth is multform” is the ritual incantation I always invoke on these occasions. Myth isn’t history; it’s more like quantum physics, where Schrödinger’s cat is both alive and dead until you open the box. Sigmund both is and is not the slayer or Fafnir, until you begin telling (or reading) a particular story. At that point the storyteller usually (not always) picks a version and sticks with it, a process analogous to wave-form collapse in quantum physics. Audiences of myths have the luxury of enjoying, even insisting on, particular versions (like toxic Star Wars fans). Students of mythology have to be sensitive to multiple versions and beware the temptations to over-historicize a particular rendition of a myth.

Anyway, in the story of Beowulf, it makes sense for the praise-singer to associate Sigmund with Beowulf. Sigmund famously killed a monster; Beowulf has just earned fame by killing a monster (Grendel). And the Beowulf-poet can use this celebration of young Beowulf’s victory to foreshadow old Beowulf’s final battle where he kills and is killed by a dragon. In fact, the Sigmund story might help explain old King Beowulf’s strange behavior toward his last enemy, how he insists on going alone against the dragon (just as Sigmund did) to earn treasure (just as Sigmund did).

I mostly like what Heaney does in his translation, but there was one part of this passage that I wasn’t crazy about.

The Beowulf-poet, describing how Sigmund slew the dragon says this:

hwæþre him gesǣlde, ðæt þæt swurd þurhwōd

wrǣtlīcne wyrm, þæt hit on wealle æstōd,

dryhtlīc īren; draca morðre swealt.

—Beowulf 890-892

“Nevertheless it befell him that the sword passed through

the wondrous worm so that it on the wall stood fixed

the illustrious iron; the deadly dragon died.”

Here’s what Heaney does with it.

“But it came to pass that his sword plunged

right through those radiant scales

and drove into the wall. The dragon died of it.”

Better than my dry literal version, certainly. But here’s Raffel’s (1963) version.

“Siegmund had gone down to the dragon alone,

Entered the hole where it hid and swung

His sword so savagely that it slit the creature

Through, pierced its flesh and pinned it

To a wall, hung it where his bright blade rested.”

Because Raffel is not binding himself to translate line by line (as Heaney does), his version rocks a little better, I think.

I’ll probably stick with Heaney. It’s still fresh, represents the original pretty well, and has a couple of different editions with distinctive advantages: one accompanied by the Old English text, another illustrated with copious images of the physical culture of northwest Europe in the early Middle Ages–weapons, jewelry, manuscript paintings of monsters, etc.

Still, I always try to keep the alternatives in mind. Myth is multiform, and every translator is a traitor. I can only be faithful to the original if I at least flirt with alternative translations.

Mirrored from Ambrose & Elsewhere.

Saw the article below on Bluesky and felt the irritation that almost always accrues when scrolling through social media. But this irritation was really specific. Demanding a historically accurate version of a myth is like trying to find the zip code of Ásgarð. It misconceives the whole enterprise of storytelling. It Must Be Stopped.

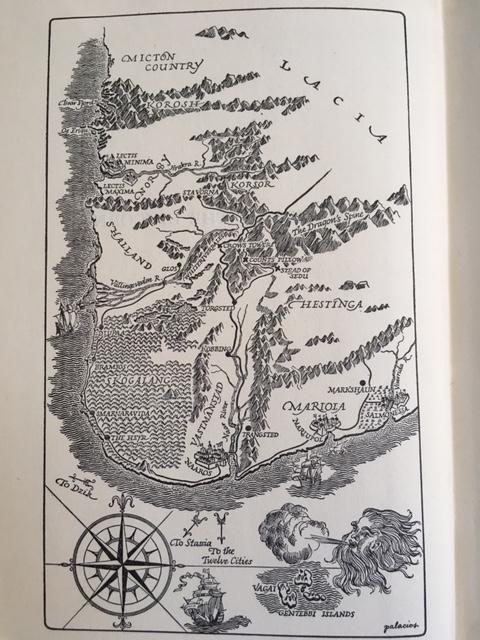

This got me thinking about maps in fantasy novels, because that was one way to avoid useful work.

Maps are really not as necessary for fantasy novels as people sometimes pretend, although I sympathize with readers who want to know how you get from the Lantern Waste to Ettinsmoor, etc. As a rather shifty storyteller, I’d prefer not to be pinned down if I can avoid it. (I always cite Melville on this point: “It is not down on any map. True places never are.”)

But I really resist the modern tendency to make fantasy maps follow modern standards of cartography and geology. That’s like insisting that the Fellowship of the Ring should have taken public transit from Rivendell to Mordor.

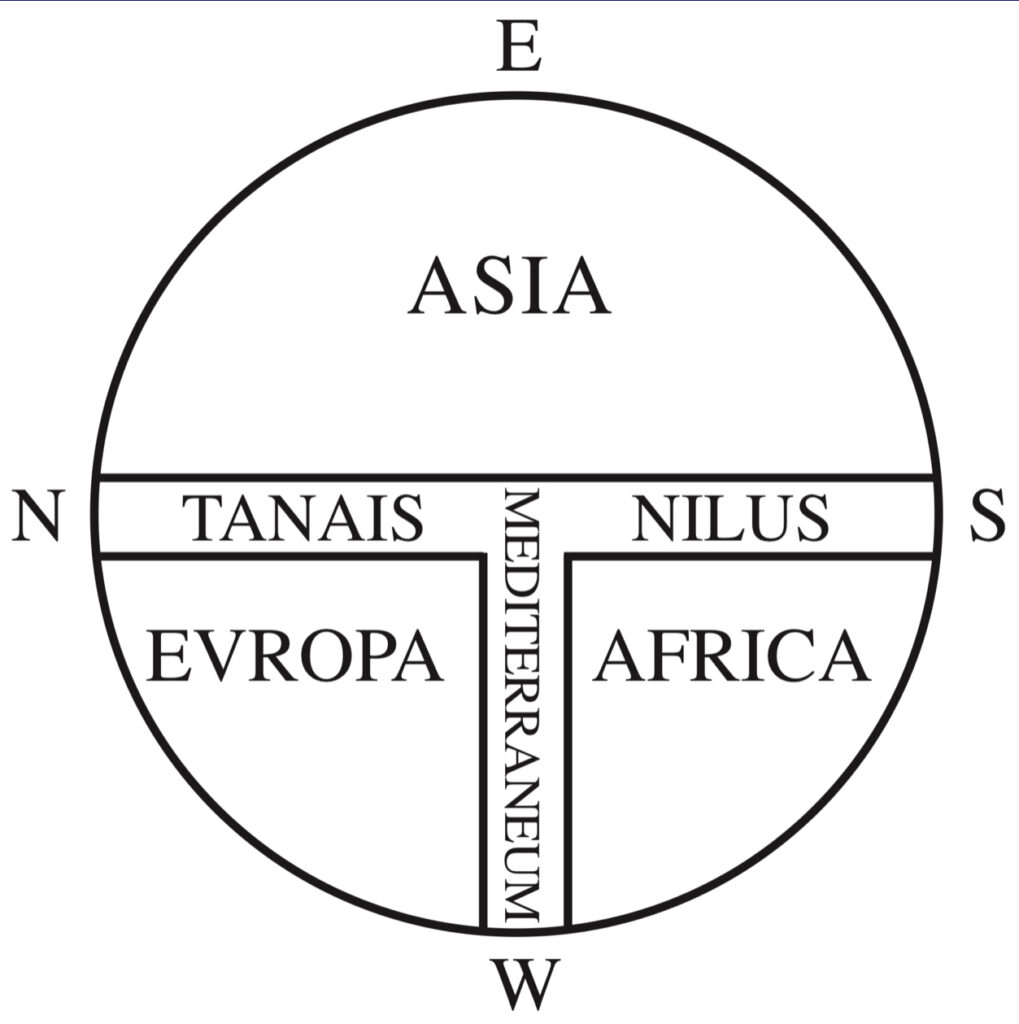

Conventions of maps vary from culture to culture, and they often don’t look familiar to us at all. In this context I often have occasion to think of this medieval model:

Or a late-Roman map, the Tabula Peuteringeriana.

Plus, there’s no reason to suppose that a fantasy world was formed along scientific principles. Imposing contemporary standards of geology onto fantasy worlds makes fantasy into a subgenre of science fiction, whereas the reverse is obviously true.

If people want to write a kind of mundane fantasy with low or no magic, that can obviously be done and has been done with great success. Pratt’s The Well of the Unicorn is a celebrated example. (Magic exists in the world of the book, but it reads like a historical novel for an imaginary world.)

This isn’t an obligation built into the genre, though. Like everything in an imaginary world, maps, the type of maps, or even the mappability of the world should be a deliberate choice on the part of the worldmaker, not something just thrown in because that’s the way it’s done, or to satisfy specious notions of accuracy.

Let us close with a hymn from the sacred texts.

“What’s the good of Mercator’s North Poles and Equators,

Tropics, Zones, and Meridian Lines?”

So the Bellman would cry: and the crew would reply

“They are merely conventional signs!”

—Lewis Carroll, The Hunting of the Snark

Mirrored from Ambrose & Elsewhere.

I was thinking the other day about Hengist and Horsa, the two Saxon chieftains/gangsters who show up to assist and then overpower the usurper Vortigern in the run-up to King Arthur’s origin story. Horsa (Horsus in Geoffrey of Monmouth’s Latin) clearly means “horse” in modern English, but WTF is a hengist? Turns out that also means “horse” (going back to Proto-Germanic *xanxistaz; so says Orel). Horsa doesn’t really do much in the story; Hengist always takes the lead, bringing in Saxon goons and becoming Vortigern’s father-in-law, and in general making V’s life a living hell.

I wonder if “Horsa” didn’t start life as a more-transparent translation of Hengist’s name (“Hengist–i.e. Horse”), and then the name got promoted to full personhood by a storyteller who didn’t know the two words meant effectively the same thing.

Vortigern’s situation with the Saxons reminds me of a “bust out”, where organized crime infiltrates a business and then runs it into the ground (e.g. the Sopranos episode 2.10 “Bust Out”). Fortunately that situation could never happen to the U.S. govt. I guess.

Another thing I found out while horsing around was that English horse is cognate with Latin currere “to run” (going back to PIE *kers- “run”). Which makes sense, since initial k sound in Latin often corresponds to initial h in English (cf English horn and Latin cornu).

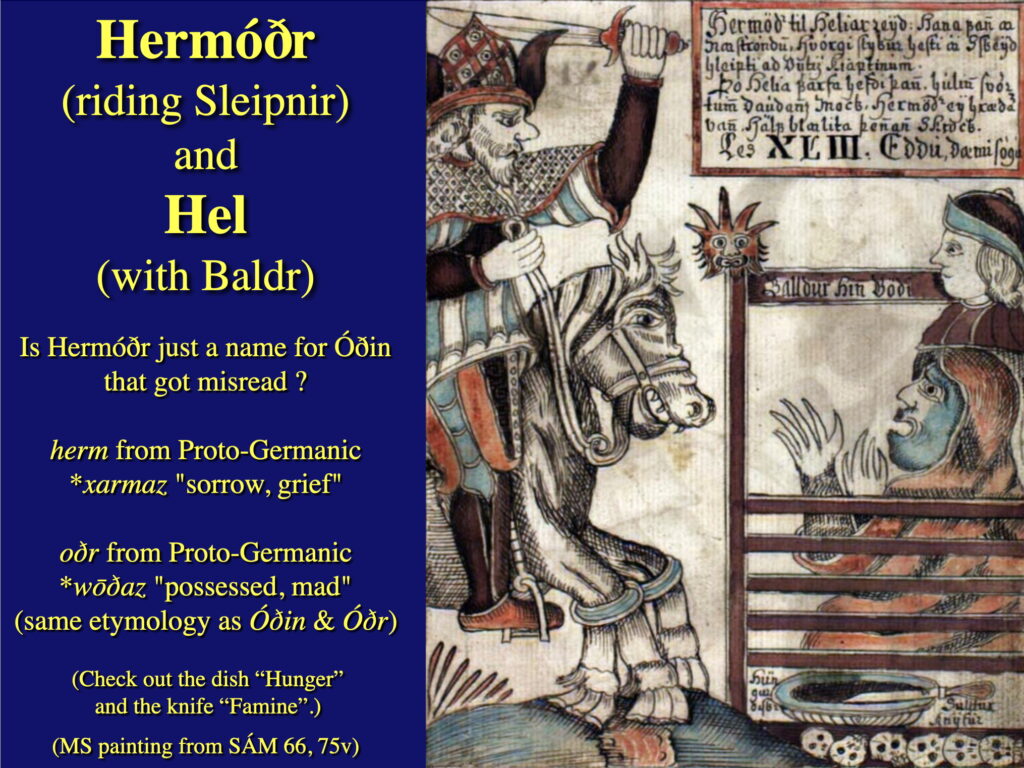

The h/k correspondence got me thinking about Hermóðr, Ódin and Frigg’s son who borrows Sleipnir, his dad’s eight-legged horse. The -óðr is pretty clearly the same root as in Óðin’s name, but what would *kerm- mean in Proto-Germanic or PIE? I looked it up in Orel’s Handbook of Germanic Etymology and it sort of snapped into focus.

Maybe there is no Hermóðr really. Maybe it’s just another name of Óðin that Snorri hypostasized into a son of Óðin. That’s explain why he’s riding Slepnir, among other things.

So my Norse Myth students got a generous side-portion of Germanic philology yesterday.

Mirrored from Ambrose & Elsewhere.

I realized this weekend that one of the pleasures of inventing a Martian language was coining new names for all the planets. (Including ones that don’t really exist, like Vulcan, Antichthon, and the Lost Planet that was once supposed to be the precursor for the asteroids.)

I think this version of the Solar System will have 12 planets, including Pluto & a trans-Plutonian planet. 12 is a magic number & if I end up wanting to add a 13th or even a 14th planet, that’s still a dozen (cf the baker’s dozen, the “12” Olympians, tribes of Israel, apostles, Labors of Herc, etc).

This made me nostalgic to read Rocklynne’s The Men and the Mirror (Ace, 1973), which includes one of the few stories written about Vulcan (not Spock’s planet, but the planet that was briefly believed to exist closer to the sun than Mercury). My sword-and-planet version of Vulcan will have to be different–possibly an invisible and/or dirigible planet.

Mirrored from Ambrose & Elsewhere.

Typos of the day, from trying to type Batgirl in a hurry on a small screen: Vatgirl and Gatgirl. Both of these sound like they belong to the Legion of Regrettable Supervillains.

Mirrored from Ambrose & Elsewhere.

I was posting lately on a corporate social media site this AM and I blithely wrote something like, “My New Year’s resolution this year is to blog more and post on social media less.” This was kind of a lie, because I don’t really make New Year’s resolutions. But it was another kind of lie, because I’ve been posting on Bluesky daily but I haven’t updated my blog in more than a week. So here I am doing that.

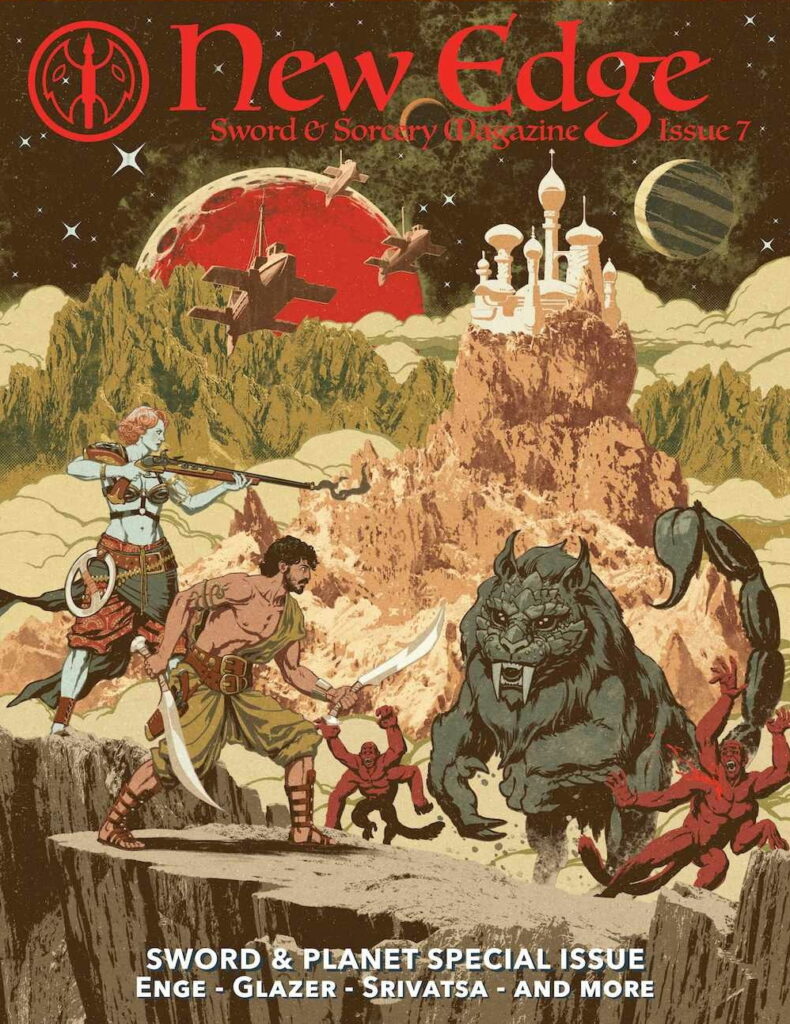

I also have some news: two new stories slated to come out this year–neither of them, oddly, Morlock stories. One is for a still-secret sword-and-sorcery anthology which will come upon you like a thief in the night, but the other is a sword-and-planet story set on Mars. It’ll appear in issue 7 of New Edge Sword & Sorcery, a special sword-&-planet issue.

Mirrored from Ambrose & Elsewhere.

I used to hold the unproven and unprovable belief that old age magnifies moral qualities, so that past a certain point you become more and more evil as you age, or the opposite. I’m not noticing any haloes when I look in the mirror, lately, so I’ve started to hope that I was wrong about that. But there does seem to be a thing that happens to some men in middle-age and afterwards, where they give themselves license to do terrible stuff because they figure they can get away with it.

Finding out that one of your heroes is a member of the club of horrible old men can be disturbing in a distinctly painful way. I’m not feeling that regarding Neil Gaiman (whose success I have always found somewhat bemusing), but the work of Woody Allen and Isaac Asimov was once deeply important to me, so I feel a degree of sympathy. You have to uproot a part of yourself to get past this stuff.

Don’t read Lila Shapiro’s meticulously reported account if you’re not ready to confront some explicit and repugnant details about Gaiman’s sexual behavior (and how his ex-wife Amanda Palmer enabled some of it). But if you can stand that, I think it’s worth reading and reflecting about what makes these men so horrible.

https://www.vulture.com/article/neil-gaiman-allegations-controversy-amanda-palmer-sandman-madoc.html

There are horrible old women, too. Marion Zimmer Bradley and Alice Munro come to mind. It’s the horrible old men who concern me more, though–maybe because the way society is set up allows them to do more damage.

Mirrored from Ambrose & Elsewhere.