The Re-Mazing Spider-Man

Jul. 11th, 2012 02:56 pmI went to see The Amazing Spider-Man last weekend, like millions of my fellow Americans, some of whom had seen it before.

Sometimes I felt like I’d seen it before, too–but as someone who’s been following Spidey’s career for well over 40 years (albeit intermittently and lazily, since that clone-saga-thing) I have a high tolerance for repetition. On balance, I liked it a lot.

My sort-of-review below the jump.

_____

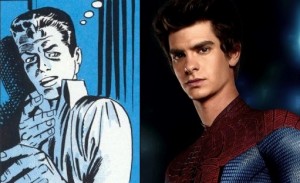

The best thing about the movie was undoubtedly Andrew Garfield’s performance. It was animated and geeky and emotional.

In passing: I’ve seen a lot of people praising Garfield by slamming Toby Maguire’s performance, but I think that’s ridiculous. Maguire didn’t write the incarnate dumbness that was Evil Disco Peter Parker–he was just the guy under contract to play it somehow. He did a great job in Spider-Man and the sequels are Not His Fault. (I’m sure the paycheck helped console him.)

But Garfield is really good–like a Steve Ditko drawing come to life–all the way to life.

Garfield never once convinced me he was a teenager. (He’ll be 29 this year.) But if there’s some time-lapse in story chronology between this movie and the next one, that’ll be less of a problem. He was really good at acting like a teenager, particularly one suffering from the gangly awkward geekitude that was always the Peter Parker trademark.

The supporting cast is also good–the standout being Denis Leary as the irascible Captain Stacy.

The plot is ridiculous in the manner of a comic-book movie, because it’s a comic-book movie. But it looks like they’re writing it less as a series of standalones than as a trilogy. (The director is Marc Webb, insert joke here, but I refer to the film-makers as “they” because this is obviously not the sort of movie where one person’s artistic vision reigns.) Rest assured that the Lizard and his evil reptilian ways will be defeated by Spider-Man and his plucky girlfriend. But, for instance, the plot of Who Killed Uncle Ben–though carefully woven into the story of this movie, is left unresolved.

Also, much of the movie’s action takes place at Oscorp, and Norman Osborn (apparently suffering from some debilitating illness–or is it his son who’s the sufferer?) is mentioned several times. But he only appears once, as a shadowy figure in the inevitable teaser plonked down among the credits. (I was hoping Nick Fury would show up and reject Spider-Man’s application to the Avengers, but you can’t have everything.)

In the new movie, Peter’s father was the guy who actually developed the radioactive spider that will eventually bite Peter. He worked for Oscorp, crossed Norman Osborn somehow, and then he and his wife were killed (OR… WERE THEY?) in a plane crash (OR… WAS IT?). I like this and I hate it. In a decade-plus, with thousands of these spiders working away in Oscorp, no one else has been bitten by them? (OR…. HAS SOMEONE BEEN?) Or maybe Richard Parker use his own DNA (and/or his wife’s) to develop the cross-species-magic-nanotech-radioactive spider, and that’s why Peter alone is affected this way. (OR… IS HE… ALONE?) (SHOULD I… STOP DOING THIS?) (O…. KAY!)

In any case: they’re leaving some questions open to build at least a 2-movie, maybe three-movie plot arc–in the shadow of the bat, as all superhero movies are these days. That’s a good thing, I’d say, as long as they don’t surrender to the temptation to make the middle movie mere filler.

(Middle elements in a trilogy can be a pain-in-the-ass to write. Don’t ask me how I know this.)

The tragedy of Uncle Ben suffers a little by comparison to the Sam Raimi Spider-Man, partly because, here, it’s left as an open case, partly because the present movie has to zag where the original movie zigged. Uncle Ben, ably played by Martin Sheen in irritating dad mode (my children laughed appreciatively at these parts, for some reason), doesn’t say anything as memorable as “With great power comes great responsibility.” Instead he sputters something like, “I believe that people with the ability to do good things have a responsibility to do them”, which sounds like a Google-translate for something that was much crunchier in the original Latin. Also he leaves a phone message that Peter gets after his death where he concludes, “You are my hero.” This is touching in a Hallmark Card sort of way–not so much in a Cliff-Robertson-struggling-to-say-his-last-words-and-letting-go-of-Peter’s-hand-as-he-dies way.

Similarly, there’s a clumsy echo in the new movie of the scene in the older movie where the common people take the part of Spider-Man. “You mess with one of us, you mess with all of us!” one guy shouts.

The parallel scene in this movie is when a crane operator whose son Spider-Man saved earlier sees that Spider-Man is wounded and can’t websling with his usual agility, but he needs to get to Oscorp in a hurry because of a ticking bomb scenario. So the crane-operator gets his fellow crane operators to swing out their cranes to give Spidey a clear path to follow.

I’ll pause to let you wipe the tear from your eye.

In general, when the movie ignores the fact that there have been other Spider-Man movies and just does it’s own spider-thing, it works really well.

The look of The Amazing Spider-Man is very warm and retro. Even the cold dirty water of the East River running under the Williamsburg Bridge at night has a warm blue Mediterranean glow.

I was pleased that they went back to the source material and made Gwen Stacy the high school sweetheart of Peter Spider-Park, as God and Stan Lee intended. The vibe between Stone’s Gwen and Garfield’s Peter was plausible and convincing. I’m afraid she’s slated for a refrigerator in a future installment… but there are worse fates for a young actress in a superhero series, as Kirsten Dunst could explain.

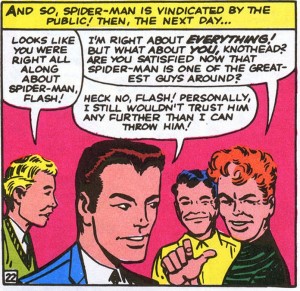

Another successful use of the original material is the arc of the Flash Thompson character. He is a bully in this movie–later he reaches out to Peter in his grief, still later reveals himself to be a fan of Spider-Man. In the brief screen-time allotted to this tertiary character, he underwent a plausible and moving transformation. And this is not the sort of thing you have to have read the old books to get: it’s all there in the movie, and it works.

In summary: People who don’t like comic-book movies will not find this to be the movie that changes their mind. People who do like comic-book movies will love this one, and they’d been ungrateful bastards if they didn’t.

Mirrored from Ambrose & Elsewhere.