I’ve been following with interest Steven Silver’s great series of reviews of the Tor Double books at the Black Gate. His latest, scrupulously fair, review of Brackett’s The Sword of Rhiannon+de Camp’s Divide and Conquer reminded me of one of my favorite Latin sayings: de gustibus non disputandum est. Or, in the words of a cinematic classic:

Michelle (Robyn Paris) in The Room (2003)

People get to like what they like and not like what they don’t like. Personally, I like The Sword of Rhiannon (a.k.a. Sea-Kings of Mars) a lot; it’s my favorite of Brackett’s sf/f novels. But I hadn’t reread it in a while, so I thought I’d see if I still found it good. (Spoilers: I did. Details and complications below.)

In the course of the reread, I thought of a much more effective pairing for Brackett’s novel: Zelazny’s Isle of the Dead. Both the Zelazny and the Brackett share the same conceit (men who overlap with gods), and they share some other weaknesses and strengths—so much so that I began to think that Isle of the Dead was at least partly inspired by and in response to The Sword of Rhiannon, something that had never occurred to me before.

First up: my thoughts about the older book, then the later, and finally some points of comparison.

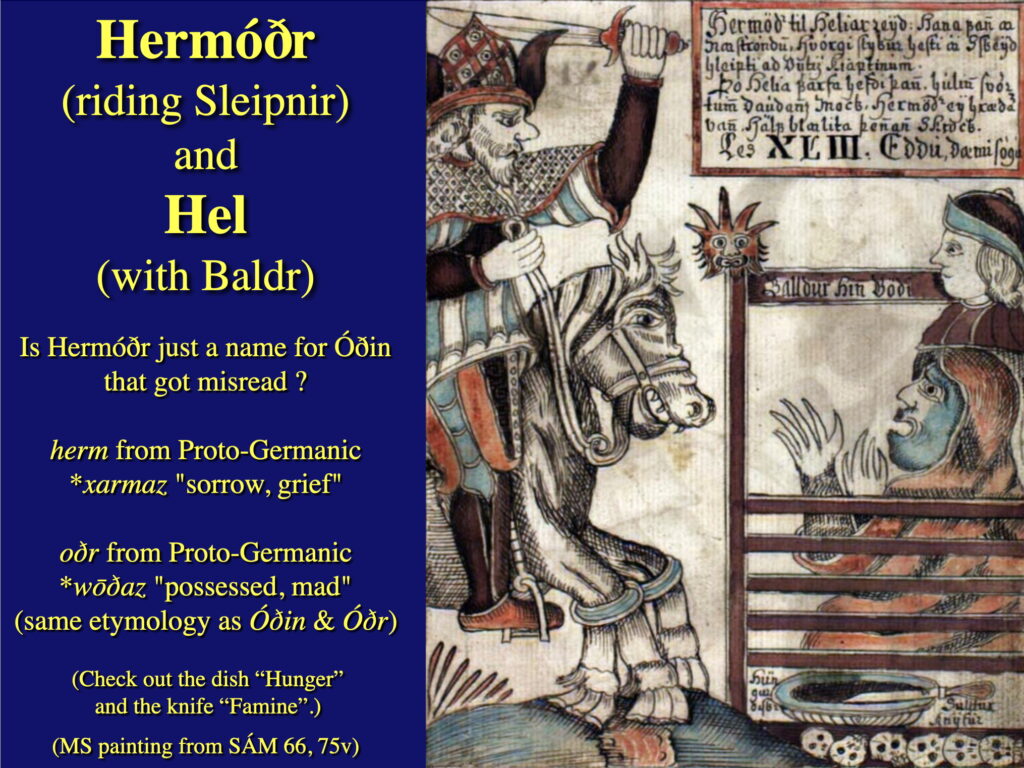

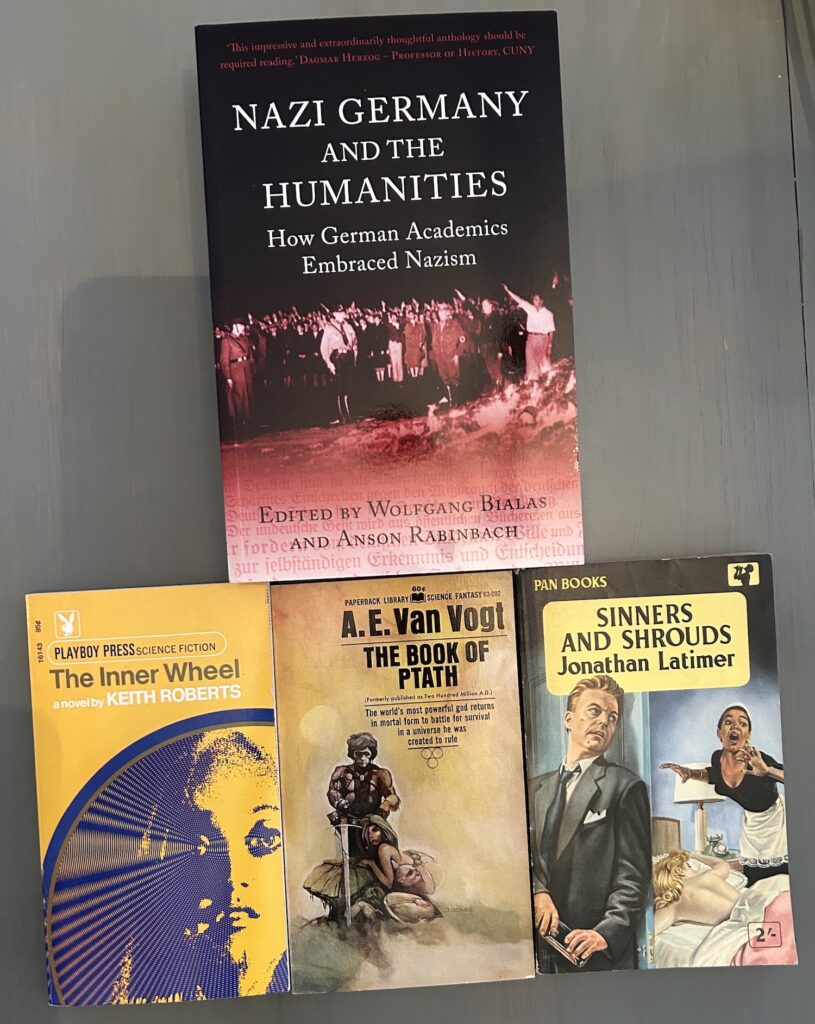

Re titles: Brackett’s book first appeared as a “Complete Novel” in the pulpy pages of Thrilling Wonder Stories (June 1949), under the title Sea Kings of Mars. It appeared a few years later in an Ace double as The Sword of Rhiannon (backed with REH’s Conan the Conqueror), and later editions always carried the Sword of… title in Brackett’s lifetime, so we can assume that it was the author’s preferred title. Sea Kings of Mars has a Burroughsian clang to it, but the Sea Kings are secondary or even tertiary characters in Brackett’s book. Rhiannon and the man he haunts are at the center of the story.

The man in question is Matthew Carse. He’s an Earthman, but he’s spent most of his 35 years on Mars. He was trained as an archaeologist but (like Indiana Jones and Belloq) has “fallen from the purer faith” and is now a thief and a tombarolo. A weaselly Martian guy named Penkawr tracks him down in the mean streets of Jekkara, one of the most dangerous of the Low Canal towns of Mars.

Brackett’s Mars is one of her greatest creations: a desert planet laced with canals, in the spirit of Percival Lowell and ERB; a planet dying but not dead; a planet that suffers under the colonial power of Earth.

Penkawr needs Carse because of his skills as an archaeologist and a crook. The Martian has discovered an unbelievable find: the tomb of dark Rhiannon, villain-god of the ancient Quiru, lost for more than a million years. Penkawr knows that he can’t safely dispose of the tomb’s fabulous treasures, so he proposes a partnership to Carse. And he proves his claim by handing Carse the most fabulous of the aforesaid treasures: the sword of Rhiannon.

Carse agrees, insisting on a two-thirds share.

“<Penkawr> turned and fixed Carse with a sulky yellow stare. I found it,” he repeated. “I still don’t see why I should give you the lion’s share.”

“Because I’m the lion,” said Carse cheerfully.”

Penkawr: not so cheerful. When they get to the tomb of Rhiannon, he shows Carse a disturbing mysterious globe of darkness. While Carse, reverting to archaeologist mode, is rapt in wonder, Penkawr pushes him into the globe. The thief figures he can make a better split with a less leonine partner.

Carse, meanwhile, falls through space and time, haunted by a terrifying presence in the darkness. He comes to himself in the tomb of Rhiannon but now, as he swiftly realizes, it’s a million years in the past. Instead of a dying, desert world, Mars is a green world rich and waters, being fought over by savage kingdoms, who have lost or never possessed most of the technology of the ancient, godlike Quiru.

Carse returns to a Jekkara a million years younger than the one he knew. In the older city, he was a respected member of the aristocracy of thieves. In this young, vibrant Jekkara he is instantly loathed because of his skin color. A mob attacks him because they believe he’s from Khondor, an alliance of piratical sea-kings with whom the Sarks and their subject cities (including Jekkara) are at war.

Carse is saved by a wily, fat rascal named Boghaz Hoi. This guy hails from Valkis and he has, as he says, “my own reasons for helping any man of Khond”. He’s also a thief and he recognizes the stuff Carse has as worth stealing. Once he examines it closer (having knocked Carse cold for the purpose) he realizes that they are relics of the sinister villain-god Rhiannon, already an ancient and mythical being in this much-younger Mars. When Carse comes to himself, Boghaz tries to persuade Carse to lead him to the tomb of Rhiannon, much as Carse persuaded Penkawr to do earlier in the story (and a million years later in history). But Carse is stubborner than Penkawr, and Boghaz too; they are still discussing the matter when they are arrested by the soldiers of Sark.

The Sarks put both Carse and Boghaz to work on one of their galleys, which is conveying Lady Yvain back to her tyrannical father, Garach, King of Sark. Scyld, the captain of the ship, claimed Carse’s valuables as his own, including the sword of Rhiannon, which Scyld does not recognize.

Is this the end of the story? Will Carse and Boghaz end their days chained to an oar in this slave-ship? Obviously not. But it’s a handy place for Carse to learn something about this world, so different from the Mars where he grew up.

For one thing, there are a number of nonhuman species in this world, the Halflings. The godlike, yet human, Quiru created Swimmers (amphibious pseudo-humans who can breathe under water), the Sky Folk (winged semihumans who can fly), and the snakelike Dhuvians, collectively known as the Serpent. Their distinguishing characteristics of the Dhuvians are high technology and evil.

Before the godlike Quiru left Mars, they imprisoned Rhiannon in his tomb as punishment for a terrible crime. The crime was lifting up the Dhuvians and gifting them with some portion of his scientific and technical knowledge. It is the Dhuvians who are the sinister power behind the empire of Sark, through which they hope to conquer and enslave the world.

Carse eventually comes to realize that, when he passed through the time portal in Rhiannon’s tomb, the villain-god attached his mind to Carse’s so that he escape imprisonment in the black globe. Rhiannon periodically begs Carse to help him do something, but Carse rejects him—until he realizes that what Rhiannon wants is to destroy the Dhuvians, undoing the crime for which the Quiru imprisoned him.

Without going into spoiler-laden details, it suffices to say that Carse and Rhiannon, working alone or in tandem, succeed in destroying the Dhuvians, breaking the power of Sark, and freeing the subject cities like Valkis and Jekkara from the Sarks’ imperial dominion.

You practically can’t have a sword-and-planet story without a space princess. As someone once put it, the original template for the sword-and-planet story as defined by the Procrustean bed of ERB’s A Princess of Mars was: “a lone American (not a Canadian–not a Ugandan–not a Lithuanian–an American) is mysteriously plunged into an exotic other world which is both more advanced and more primitive than the earth he knows. He conquers all by virtue of his heroism and marries the space princess.”

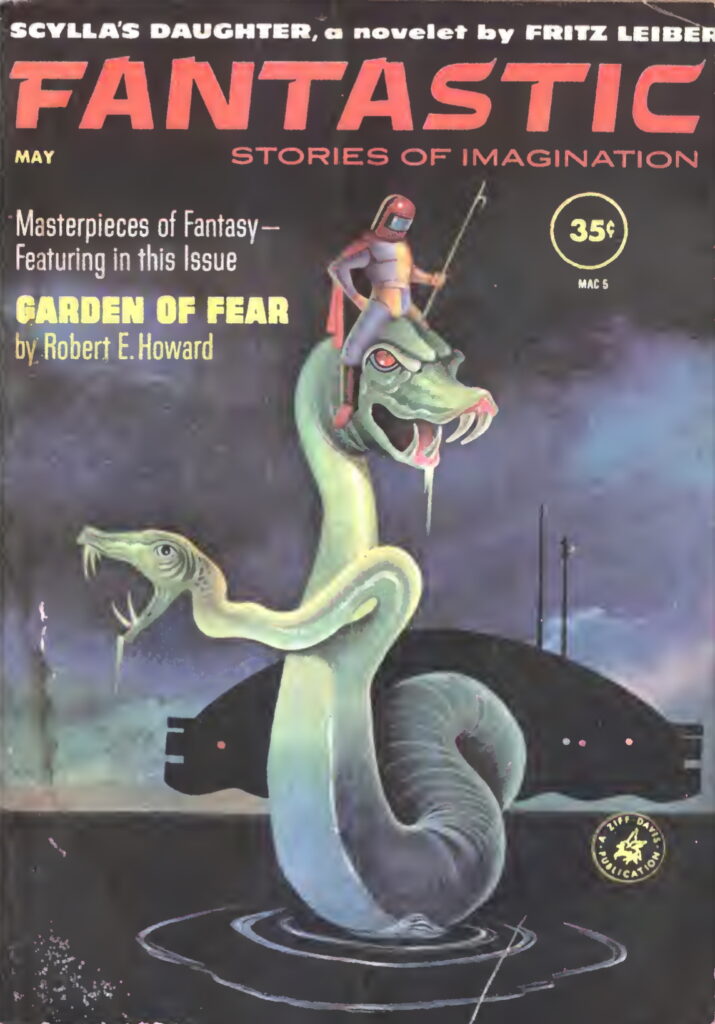

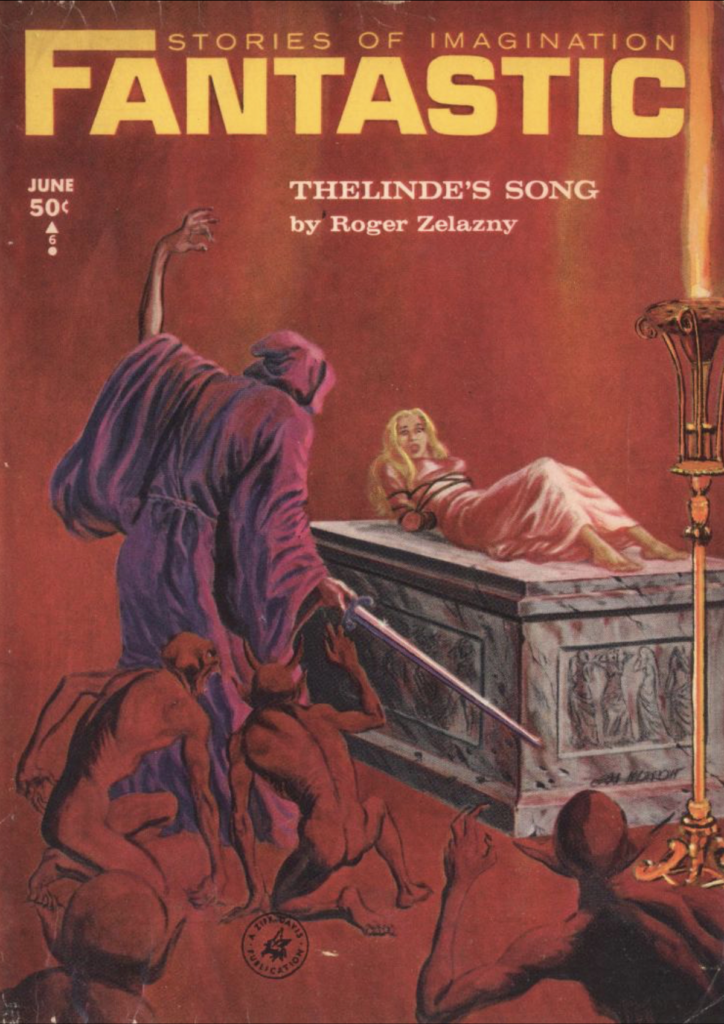

Sword-and-planet became a more varied genre by the 1940s-1950s; Leigh Brackett herself helped to stretch the boundaries. But there is a space princess in this story, Yvain of Sark, and it’s not really a spoiler to let you know that Carse and her end up together despite some early antagonism. They end up fighting side-by-side against the Dhuvians. (That’s them on the cover of Thrilling Wonder Stories above.) Yvain is a likably tough and free-minded character, not just a storytelling cliché; she could easily be the protagonist of her own story.

In heroic fantasy, it’s not uncommon for the hero to kill the bad guy. In sf of the 1930s-1940s, the bad guy is frequently a nation. In heroic fantasy which is pretending to be science fiction (a decent quick-and-dirty definition of sword-and-planet), would the hero kill an entire nation or species?

Obviously not. Genocide is immoral, consequently not heroic. Right?

Right, but genocide is the happy ending of many a story in old-school space opera. Consider the Lensman series by E.E. “Doc” Smith, where it is frequently the task of the heroes to wipe out entire species, like the Overlords of Delgon, or the unspeakable Eich, or the shapeless amoral monsters of Eddore.

It’s Rhiannon, rather than Carse, who imposes the Final Solution on the Dhuvians, so one could argue that Carse is not responsible. But it’s Carse and the other protagonists who benefit. All faves are problematic faves, as we know (or used to). This is the most problematic element in this fave for me. It works in the universe of the novel because the Dhuvians are established to be 100% bad. In the real world, that’s a racist idea that should never pass by without being challenged.

A less serious problem—maybe not a problem at all—are the naming conventions. If you know anything about Welsh myth or Arthurian legend, you’ll be surprised to find Rhiannon a man (or a male, anyway) and Yvain a woman. Then there’s Scyld—but a book could be written, maybe should be written, about names in heroic fantasy. For the time being, when confusion arises, I recommend banishing it by chanting the wise words of an ancient song:

“repeat to yourself it’s just a show; I should really just relax.”

Boghoz Hoi is worth a mention before I move on, too. He’s a worthy addition to the long tradition of cowardly, selfish, semiheroic sidekicks going back to Falstaff, at least, and including space opera characters like Giles Habibula from Williamson’s The Legion of Space.

Another thing that cries out for mention when discussing Leigh Brackett is her absolute mastery of style. This doesn’t matter to some readers; the text is just a screen through which they see the story. They don’t hear or see the shape of the words. But for those that do, reading Brackett is like listening to music.

Here’s the moment when Penkawr shows Carse the sword of Rhiannon:

The thing lay bright and burning between them and neither man stirred nor seemed even to breathe. The red glow of the lamp painted their faces, lean bone above iron shadows, and the eyes of Matthew Carse were the eyes of a man who looks upon a miracle.

You either like this sort of thing or you don’t. If you like it, you will like this book a lot.

As noted above, the Tor Double paired Brackett’s short novel with another by de Camp, but a better match (it seems to me) would have been Zelazny’s Isle of the Dead (Ace, 1969).

snerged from Wikimedia

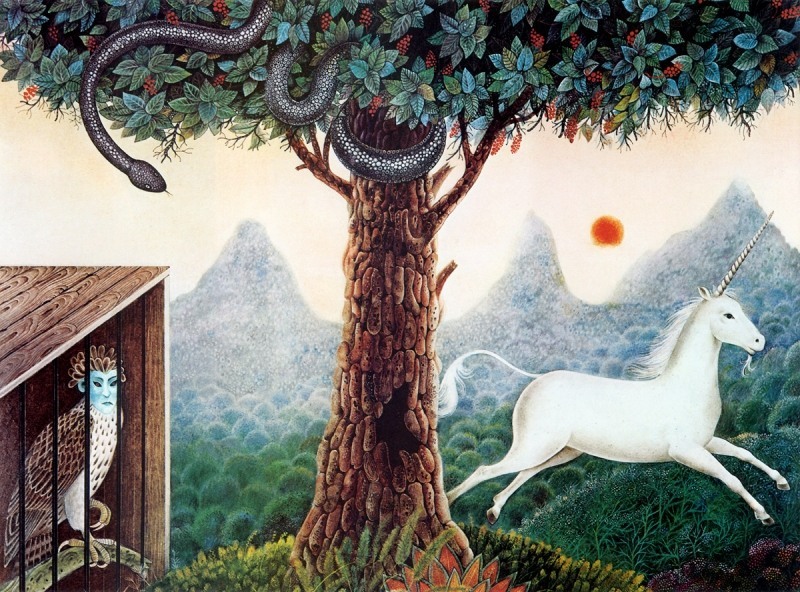

Isle of the Dead is a multi-media experience. There’s the original paintings (sic: multiple versions) by Böcklin. (See above.) Then there’s Rachmaninov’s tone-poem inspired by the painting.

There’s a pretty good Val Lewton film, starring Boris Karloff, that makes use of the same setting. The monster in this film is a real one, and very timely: a crazy person who forces people to live and die in accordance with his demented ideas. Boris Karloff plays the RFK jr. role in this classic.

Last and (honesty compels me to admit) least there is Zelazny’s Isle of the Dead, a heroic fantasy pretending to be science fiction.

Center: J.H. Breslow’s cover for a later Ace edition (1974).

Right: Philippe Caza’s cover for the French translation ( J’ai Lu, 1993).

All snerged from ISFDb.

Is Isle of the Dead sword-and-planet? The way I just described it may imply “yes”. Others might say “no”.

This is, one might argue, a pretty standard science-fiction novel by the standards of the 1960s, featuring a high-technology culture with frequent space travel. How could a science fiction novel with realistic technology like FTL ships, laser weapons implanted in fingertips, and resurrection technology possibly qualify as a kind of fantasy?

Well: remember that not-exactly-serious definition from above: “a lone American (not a Canadian–not a Ugandan–not a Lithuanian–an American) is mysteriously plunged into an exotic other world which is both more advanced and more primitive than the earth he knows. He conquers all by virtue of his heroism and marries the space princess.”

The hero is an American from the late 2oth century. He is plunged into an exotic future world by a series of STL interstellar voyages, during which he is in suspended animation. He finds himself in a universe which is more advanced than the one he came from (the aforesaid FTL ships etc), but also more primitive: the most advanced people in the galaxy, the Pei’ans, live in a low-tech environment, engage in something very like magic, and practice an ethos dedicated to elaborate revenge. There’s even a space princess in the story, who the hero ends up with. So maybe this story is sword-and-planet, or at least adjacent to it

The hero, Francis Sandow, learns the wisdom of this ancient race and becomes a Dra—both a priest in the ancient Strantri religion, and a worldmaker—someone who can use tremendous technological and personal forces to reshape worlds. This is a godlike power, and each Dra is associated with one of the countless gods of the Strantri religion in a mystic ceremony where the would-be Dra and the god become entangled with each other.

Sandow is a reasonable person, even and you and I are, and he doesn’t believe this nonsense for a moment. The stuff about being a god is just metaphorical: “It is a necessary psychological device to release unconscious potentials which are required to perform certain phases of the work <of worldbuilding>. One has to be able to feel like a god to act like one.” As far as Sandow is concerned, Shimbo, Shrugger of Thunders, whose image lit up when Sandow passed it during the confirmation ceremony, is just a figment of his imagination—a mask he wears, a tool of his trade, not a god.

Maybe so. But others feel differently. Shimbo has an ancient enemy among the gods: Belion the Destroyer. Gringrin Tharl, a Pei’an fundamentalist, who resents the revisionist attitude of Sandow and the other worldmakers, undergoes the confirmation ritual and becomes identified with Belion. Then Gringrin (or Belion) launches on a centuries-long quest for revenge against Sandow, who doesn’t even know he exists. This climaxes when Gringrin (or Belion) kidnaps a half-dozen of Sandow’s friends, lovers, and enemies, both living and dead, and challenges Sandow to come and get them from the Isle of the Dead.

This not being a fantasy novel (unless it secretly is), the Isle of the Dead is located on a world named Illyria which Sandow himself created on commission centuries before. Gringrin/Belion acquired it and has been corrupting it as part of his/their revenge against Sandow/Shimbo.

In the end, Sandow has to go alone, on foot, to the river Acheron and the Isle of the Dead to confront his enemy, who is wearing a face he will not expect.

This is the summary of a ripping yarn, in my view. Does Zelazny actually deliver one?

Well, yes and no. Zelazny has to get his hero from a mundane world to a magical one (cf Nine Princes in Amber, where Corwin wakes up in a 20th-century hospital suffering from amnesia and has to grope his way into the magical world he senses but does not understand or remember). From my point of view, this is hampered by the fact that Sandow, at the story’s beginning, is kind of an unlikable character, rich and crassly materialistic “eating fancy meals <and> spending my nights with contract courtesans” as he himself puts it.

Once he gets jolted into motion, the story works a little better for me. There is a long detour to justify the idea that Gringrin could scientifically resurrect the dead from Sandow’s past and be holding them prisoner in the narrative now. I found this somewhat tedious, and no more convincing than if a sorcerer waved a wand to get the same result. But this is the kind of narrative furniture that you stumble over when you’re dealing with one of these heroic fantasies disguised as sf.

It’s when Sandow lands on Illyria and begins walking toward the Isle of the Dead that the story really begins to fulfill its promise. Sandow considers the gods to be convenient fictions, made for the benefit of mortals. The gods themselves have different ideas, and bring the situation to mortal conflict in conflict with the wishes of the mortals involved. But, in the end, it is Sandow, not Shimbo, who strikes the deciding blow and emerges, still-breathing if badly wounded, from the final confrontation.

So: good things and bad things here. Good things include some vivid characters (especially Nick the dwarf, who blazes like a comet through the second half of the book, and the would-be Dra Gringrin Tharl who acts as both enemy and sidekick to Sandow), and some entertaining Raymond-Chandler-in-space passages filtered to us through Sandow’s narrative persona.

On the down side: Zelazny, like Brackett, was one of the great stylists of 20th-Century sf/f, but he’s not working at the top of his game here. De gustibus, etc, but I don’t find his descriptions of the Isle of the Dead anywhere near as evocative as the paintings, the music, or even the movie focused on the same scene. Zelazny also displays his willingness to go for the cheap laugh, at the expense of more important values. The planet Illyria has three hurtling moons, similar to but different from Barsoom’s. They are called Flopsus, Mopsus, and Kattontallus—Flopsy, Mopsy, and Cottontail. I can see Zelazny smiling to himself as he typed these names out, but they disrupt the heroic scene that Zelazny is setting. And the last scene of the book includes the most unforgivable line in the Zelazny canon: “Forgive me my trespasses, baby.” Urgh.

Also: Zelazny’s women tend to be malicious, to the extent that they’re not passive, and this novel is more evidence of that. Some women are passive, of course, and others are malicious. It’s the regularity with which these tropes appear in Zelazny that makes my teeth grate. In this way, Zelazny is somewhat less modern than his older contemporary, Brackett.

One of the things that makes me think that Zelazny is riffing on, or replying to, Brackett’s novel is that genocide comes up a couple of times. One doesn’t hear Zelazny murmuring, “Never again”, but at least the act is problematized in a couple ways.

Another is, as I mentioned above, the central conceit of both books, where a man acts (willingly and unwillingly) as the vehicle of a god. In both books, the man and god struggle for control. In both books, the final end is achieved only when the man and god can bring themselves to work in tandem.

And both are heroic fantasies with a candy-coating of super-science—magic, by Clarke’s Third Law.

I don’t seem to have any great thumping conclusion to put here, but maybe my patient readers feel like they’ve been thumped enough.

In summary, these works of heroic fantasy have some flaws, but remain worth reading. Forgive them their trespasses. Maybe someday someone will do the same for you.

Mirrored from Ambrose & Elsewhere.